- Home

- Jerry Sacher

Noble's Savior

Noble's Savior Read online

Published by

Dreamspinner Press

5032 Capital Circle SW

Suite 2, PMB# 279

Tallahassee, FL 32305-7886

USA

http://www.dreamspinnerpress.com/

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of author imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Noble’s Savior

© 2014 Jerry Sacher.

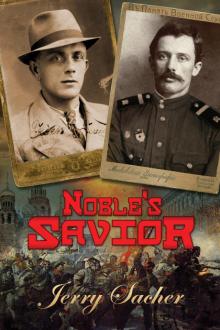

Cover Art

© 2014 Catt Ford.

Cover content is for illustrative purposes only and

any person depicted on the cover is a model.

All rights reserved. This book is licensed to the original purchaser only. Duplication or distribution via any means is illegal and a violation of international copyright law, subject to criminal prosecution and upon conviction, fines, and/or imprisonment. Any eBook format cannot be legally loaned or given to others. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the Publisher, except where permitted by law. To request permission and all other inquiries, contact Dreamspinner Press, 5032 Capital Circle SW, Suite 2, PMB# 279, Tallahassee, FL 32305-7886, USA, or http://www.dreamspinnerpress.com/.

ISBN: 978-1-62798-450-8

Digital ISBN: 978-1-62798-449-2

Printed in the United States of America

First Edition

March 2014

Acknowledgements

I WISH to thank my partner Dean Johnson for all his support and encouragement. I also want to thank my parents, Ken and Barbara; my family; and my friends. Thank you and God bless you all.

Prologue

WRONG TURNS. It was a wrong turn and two gunshots that ignited the fuse that started the World War—a number one would be added much later.

On the twenty-eighth day of June in 1914, Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie were on an official visit to Sarajevo, in the Austro-Hungarian province of Bosnia. After an initial failed attempt on the Archduke’s life, Ferdinand chose to visit the wounded officers at a local hospital. However, his motorcade made a wrong turn, and while the driver backed up the car, Gavrilo Princip—a Bosnian member of a nationalist group called the Black Hand—jumped up on the car’s running board and fired two shots. In minutes, both the Archduke and his wife were dead, and the horror of the World War was begun.

Wrong turns can also lead us in the right direction—to love and life even in the midst of violence and fear.

Chapter 1

Petrograd, formerly St. Petersburg, Russia

February 1916

BENJAMIN CARTER got up from the dining room table, walked over to the window, and lifted aside the gold damask curtains. Using a fingernail, he scratched the thick coating of frost from the glass and peered through the pinhole patch he had made. The snow-covered street outside was empty this morning.

Yesterday, a workers’ march had wound its way from the factory district, down the fashionable Nevsky Prospekt, and spilled into the side avenues of the city. The marchers’ red banners had called for an end to the war, which had been raging for almost two years now. They also wanted land and bread, which Benjamin’s father, a British diplomat to the Russian Court, said was the same song every peasant had sung since the beginning of time. What disturbed Benjamin were the weapons the workers had carried with their placards.

With the clink of a china cup on a saucer, he heard his mother’s voice behind him. “Your father thinks revolution is coming soon, but still he insists on staying on here.”

“He’s a damn good diplomat, Mother. He remains, because this is where he’s needed the most.”

“Language, young man. And I fail to see what good he can do with the tsar at the front and his wife and Rasputin running the country in his absence.”

Benjamin smiled at her in apology.

He sighed. He hated when his mother talked about the empress and her starets, or holy man, Grigori Rasputin, but the rest of the country also buzzed with rumors that the tsarina and Rasputin were spies. Whether true or not, Benjamin didn’t know or care. He wanted to join the war on the Western Front with his friends, serving in the British Army. His heart broke to receive letters from the relative of a friend or a relation back home in England that began with the dreaded words: “Regret to inform you….”

He cried whenever he thought about those handsome young men with whom he had gone to school and played cricket, now fallen on the battlefields of France. He dreamed about certain faces at night as he lay in bed—especially Reginald, the nephew of some high government official. Benjamin remembered Reginald as a tanned, handsome boy with auburn hair, who’d shared a room with him during their early days at Oxford. That, of course, was not all they had shared, but Benjamin dared not reveal that confidence.

Benjamin sat at the table across from his mother as she instructed the liveried footman to bring in breakfast. He only heard her say, “His lordship will be down directly….” He didn’t hear the rest of her words, but he was certain they pertained to her group of ladies who came each afternoon to knit scarves for the troops at the front. He knew also that they would gossip about Alexandra and Rasputin.

He had seen Rasputin a few times, riding in a Renault motorcar surrounded by his “followers,” and to Benjamin he looked like one of the peasants he had seen in the provinces working in the fields on the estate owned by a family friend. Benjamin had listened with interest to whispered conversations among Petrograd society about the tales of the holy man’s large member. The stories seemed too fantastic to believe, but he found himself curious about it. His own privates swelled just thinking about it and then fell when his father entered the dining room with a leather portfolio and a folded newspaper.

Benjamin looked up from his plate. Simon Carter looked every inch the sort of diplomat he read about in books—tall and stout, with a gray beard, and gold-rimmed glasses perched on the end of his nose. His blue eyes were sly like a fox’s, and sometimes it felt like he could see right into the depths of another person’s soul.

Today when his father came into the dining room, he looked angry, and Benjamin knew he would waste no time in making his discontent known. His father pulled his chair back from the table and slammed down the paper and portfolio.

“What’s wrong, Father? You’re in a bad mood this morning.”

“What’s wrong? The war is going terribly for Russia—the men at the front get only three bullets a day. The tsar hides among his troops and thinks it’s a good thing. Meanwhile, the empress and her monk hire ministers barely qualified to run a circus, much less a country, and all because they, too, follow the ravings of Rasputin.”

Benjamin noticed the English newspaper under his father’s hand. “What about the news from England?”

His father picked up the newspaper and handed it over.

Now would be the perfect time, Benjamin thought, to tell his parents what was on his mind, so he blurted it out without hesitation. “I want to go back and join the British Army!” He slapped his palm on the table.

His mother went pale, but his father sat back and cleared his throat. “We’ve been through this countless times, young man. I need you here in Russia with me.”

“Doing what, Father? I’m needed in the trenches in France with my friends. Here you only need me when you have important war messages from King George to deliver to the war ministry, and a boy on a bicycle could accomplish that.”

“Then you’re ‘doing your bit’ for the war effort, as you young people say

. You’re our only son. Think of your mother.”

Benjamin looked from his father to his mother across the table. “Then you would have a son who’s a coward. Is that what you want? In London, women hand out white feathers to men not in uniform.”

His mother lifted her napkin to blot an imaginary tear from her eye. His father raised his hand. “Ben, nobody is calling you a coward, but for the present, your place is here in Petrograd—”

His mother interrupted. “One hears stories coming out of France these days, and you would see such unimaginable horrors, Benjamin. I forbid it!”

His father reached out and patted her hand in sympathy. “There now, Hazel, don’t excite yourself. Benjamin will soon realize how fortunate he is to be out of the firing line.” He cast a stern glance at his son.

Benjamin threw down his napkin and stood from the table. He left the room and slammed the door behind him before stalking across the wide marble hall, which always reminded him of a museum.

The drawing room he entered forced him to think of some distant era, with its crystal chandeliers and oil paintings enclosed in heavy gilt frames. The men and women who stared at him from those old canvases made him feel their disapproving eyes upon him. He ignored them as he sat on a red-and-gold settee in front of the fireplace. On a table next to him were the only modern objects in the entire room: a gramophone with a large brass horn and a stack of records. He cranked the machine and put a record on the green felt, then lowered the needle onto the record.

A scratching noise sounded for a second, and then Benjamin laughed, imagining the horror on those faces staring from the walls as the latest music from America, called ragtime, issued forth from the horn. Suddenly the drawing room wasn’t so cold anymore. He stared into the fire, telling himself he was lucky. Outside, cold and hungry striking workers and peasants who had come to the city in search of work looked to Nicholas II—“Batushka” or “father tsar”—to help them. Instead, the tsar was hundreds of miles away, commanding his armies, leaving his ineffective wife, the Empress Alexandra, to run the government.

“It’s all such a mess. Only a magician could unravel it….” Benjamin spoke to the fire, and he was startled when his father spoke to him from the open door of the drawing room.

“If you know of one, I’ll be glad of his services.”

“I’m sorry, Father. I didn’t hear you come in.” Benjamin reached over and pulled the needle from the spinning record to shut off the machine. His father settled back in his chair.

“I nipped in to have a chat with you before I leave for the embassy. You upset your mother when you mentioned joining the British Army, but I got her calmed down.”

“It’s the duty of every loyal subject of the king to fight. It’s your duty, Father, to stay here in Russia, but mine—”

“The time will come for you to fight, and you can join the Army then. I came in here because I have a job for you. I have dispatches I want delivered directly into the tsar’s hands at Stavka in Mogilev as soon as possible. I would go myself, but I’m needed here. You can leave today if you like. The travel will give you a chance to think things over.”

Benjamin stood up and clasped his hands behind his back.

“Very well, but it won’t do any good. When I return, I’m leaving for London to join the Army.”

Chapter 2

Mogilev, Belarus

SERGEI OPENED his eyes and realized the cold, hard surfaces underneath his head and legs were railroad tracks. He lifted his head and saw himself surrounded by the casualties of war—the wounded and the dead laid out in rows of red and white, khaki and black. It took him a few minutes to realize the red was blood and the white was snow. The khaki belonged to the uniforms of his comrades, and the black forced him to think of vultures until they became the figures of nuns and doctors moving from man to man, peering into faces, and moving on. Snow was falling, and the thin blanket someone had thrown over him offered little warmth.

Sergei tried to remember what had happened before, but all he came up with was a series of images—gunfire, flying dirt and wood, men crying out and falling around him, and then something hard had struck him in the side, and he fell as well.

After rising on unsteady feet, Sergei walked toward a structure a few hundred feet ahead of him. It was a railway station.

He pulled open the rag that was the remnant of his Army greatcoat. Someone had removed his shirt, and he saw the red-stained bandage where a bullet had grazed his ribs. He pulled the wool over his muscular bare chest, more to protect the wound than keep out the biting cold.

Artillery fire had badly damaged the stone building and broken most of the windows, which they’d covered with heavy tarpaulins. The solid doors creaked open loudly, and going inside, Sergei wrinkled his nose at the mixed odor of chloroform, unwashed bodies, and the unmistakable smell of blood. In the center of the room, someone had started a fire using the benches and other furniture. Sergei stood at the blaze, warming his hands, and then in a corner he saw an officer in uniform with the armband of the Red Cross. He walked slowly over to him.

The young man at the desk glanced up at Sergei’s approach, and he laid aside the papers. Though dirt and blood covered the man’s coat, Sergei saw a captain’s insignia. He ought to salute, but Army discipline—like supplies and communications—appeared almost nonexistent here. Through tired, heavy-lidded eyes, the captain spoke gruffly.

“Well, what is it?”

“The battle, sir—have we routed the Germans?”

The captain locked his gaze with Sergei’s, and for a second Sergei thought he read something in them, but what? Disillusionment, lust, fear? Sergei ticked off the things in his mind, but the young captain sat back in the chair and blew warm air on his fingers.

“Miserable defeat is what it was. Look around you. We’ve had no supplies from Petrograd or Moscow in three weeks. Can a soldier fight with no food or rounds of ammunition?” The captain spat on the dirty carpet. Sergei stared at him silently, not really knowing how to answer. The mention of food made his stomach growl loud enough for the officer to hear. Smiling, the captain rose from the table and crouched down over a battered wooden chest in the corner. He opened it and pulled out a small burlap sack.

“It’s not much, but I brought back some tea and sugar on my last visit to Moscow. It’s all I can offer you.”

“T-thank you,” Sergei stammered and watched the officer walk over to the fire in the middle of the room. On the edge of the fire, he noticed a small grate with a brass teapot sitting on it. The officer ordered Sergei to sit on the one remaining chair in the room, and Sergei watched the man silently as he went about preparing the tea. He was glad to sit down; his wound was painful, and it felt as if it was bleeding.

Five minutes later, the hot tea, heavily sweetened with sugar, warmed his insides, and he cradled the tin Army cup to warm his fingers. The officer appeared quite amused, watching Sergei drink.

“What’s your name, soldier?”

“Sergei… Captain Sergei Breselov of His Imperial Majesty’s Horse Guards.”

“Your regiment and the rest of the Army moved on to the front a couple of days ago.”

“I’d better leave right away to join them.” Sergei set down the cup and would have risen, but weakness promptly stopped him. The captain came around the desk and pulled open Sergei’s ragged Army coat despite his protests. The wound had opened again, and the loss of blood made him dizzy, but the officer steadied him.

“I’m afraid you won’t be going anywhere for the next few days. Come with me.” Supported by the captain, Sergei followed him into a small room off to the side. The room was warmer and had a brass bed with heavy blankets, which moments later Sergei felt being piled on top of him.

A comforting voice whispered into his ear, “I’ll try and find one of the doctors. Just lie still.”

“You’re not a doctor?” Sergei spoke through chapped, fever-parched lips.

“I was studying medicine in St. Pete

rsburg when the war broke out, so I ended up here, shuffling papers and looking at wounds. Yours, by the way, has opened again, hence the fever and weakness.” The captain pressed Sergei back onto the bed and left the room.

Lying on the mattress, Sergei noticed for the first time that he heard no boom of artillery or gunfire, no sound of men screaming and dying, only the homey sounds of a clock ticking on a shelf, logs crackling in the wood stove, and voices calling out from a distance. It reminded him of the village where he grew up on the banks of the Neva River.

Sergei closed his eyes and thought about how he had ended up as another battle casualty.

IN 1913, before the war started, he had come home in a snowstorm to find the village priest kneeling over his mother’s bedside in prayer. The man didn’t look up from his Bible when Sergei came near.

“It’s all over, Sergei. She’s dead.”

Sergei sat down on the side of her bed and made the sign of the cross but did little else.

The day of the funeral, he locked the door to the cottage, mounted his horse, and rode off in the direction of St. Petersburg. He had no idea what he would do when he got there, but he had always let circumstances guide him before, so he wasn’t afraid of anything that might happen. He had mentioned joining the Army to his parents once before, and during the journey to St. Petersburg, he began to think on it again. He felt the Army might well be the opportunity he was looking for.

It took nearly a week to reach the capital, and his first sight of the city was the golden onion domes of churches shining in the sun, which broke through the dismal clouds when he approached. It reminded him of one of the dream places he’d read about in the few books that filtered in to the village school.

Sergei rode through the city, looking at the warm pastel palaces along the Neva Embankment, and the sight of the massive Winter Palace nearly took his breath away. He bowed his head when he passed Palace Square, recalling that Sunday in 1905 when members of the Imperial Guard had killed hundreds of peaceful demonstrators who had gathered to petition the tsar. Sergei had only been ten years old at the time, but the news had filtered through his village in whispers, so the landlord wouldn’t hear of their discontent. Sergei shook his head as he thought about it, and rode on.

Noble's Savior

Noble's Savior